AI Readiness and Digital Fluency: Key Insights from 133 Malaysian Professionals

- Nov 27, 2025

- 8 min read

A Survey by the Centre of Applied Metacognition (CAM) on Confidence vs. Competence

In today’s fast-changing world shaped by Artificial Intelligence (AI), digital skills are no longer optional. But how prepared and confident are Malaysians in this new landscape?

To explore this question, the Centre of Applied Metacognition (CAM) conducted a survey with 133 Malaysian working professionals, most of whom work in higher education. The survey asked participants to rate themselves, their peers, and the general public on three areas: digital fluency, familiarity with AI and confidence in learning new technologies. Participants also completed a Digital and AI Fluency (DnA) Quiz - a comprehensive assessment that measures an individual's competency and confidence in mastering key digital and AI skills.

As seen in Figure 1, the majority of survey respondents were women (69.9%). Most participants were aged between 25 and 54 years old (92.5%), and were highly educated professionals, with 82.7% holding at least a Bachelor’s degree and 47.4% holding a postgraduate degree. There were no significant gender, age or education level differences in their digital fluency scores.

Key Findings 1: Confidence is the Hidden Engine of Digital Fluency

Believing you can learn might be half the battle when it comes to mastering new digital skills.

Our survey results reveal that respondents had an optimistic and confident outlook regarding their digital capabilities. Respondents were comfortable with using AI and reported high confidence in their ability to learn new digital tools.

But how does this translate into actual digital skills? We investigated how self-perceived digital fluency affected performance on the Digital and AI Fluency (DnA) Quiz.

As expected, we found a positive correlation between respondents’ self-perceived digital fluency and quiz performance (r=0.527, n=133, p<0.001). More interestingly, Comfort and Familiarity with AI (r=0.553, n=133, p<0.001) and Confidence and Openness to Learning (r=0.545, n=133, p<0.001) also showed positive significant correlation with quiz performance.

These findings suggest that a person’s openness to learning and their self-efficacy (their belief in their own ability to master new skills) can have significant influence on their digital capability. The link between learning attitude and performance had been previously explored by Icek Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior¹ which examines how attitudes drive action, and Bandura’s Theory of Motivation², which highlights the vital role of self-efficacy in determining persistence.

Theories of Motivation & Behavior

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior by Icek Ajzen¹, our personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control can greatly impact our intention on following through on a behavioral change. Similarly, in Bandura’s Theory of Motivation², self-efficacy plays a vital role in determining how much effort one will be willing to expend on mastering a new skill, and how long they will persevere in the face of obstacles in their learning process. The stronger the sense of self-efficacy or personal competence, the greater the effort, persistence, and resilience. In other words, what we believe about ourselves strongly shapes what we do.

The Theory of Planned Behavior provides a framework for understanding how to leverage this positive mindset. As Figure 3 illustrates, our intention to engage with new digital tools can be influenced by three factors:

Personal Attitudes: People who see AI as ethical, empowering, and useful for productivity are more likely to engage with it.

Subjective Norms: When peers, friends, and workplaces actively support AI adoption, individuals feel socially encouraged to participate.

Perceived Behavioral Control: People who have exposure to AI tools and digital devices are more confident in learning new AI technologies.

Together, these factors create a reinforcing loop: positive beliefs and social approval lead to stronger intentions to learn, which increase digital adoption and skill development.

While intention and motivation doesn’t always lead to action, it is the vital first step to build a growth-oriented mindset. Nurturing a positive attitude towards learning will help individuals maintain a strong commitment to their goals, heighten their efforts in the face of failure, and encourage resilience during setbacks.

Key Findings 2: High Personal Confidence, Low National Ranking

Our survey suggests that most Malaysians are prepared and confident in taking on the challenge to master new digital technologies. This aligns with external studies³ showing that Malaysians have grown increasingly aware of AI and its potential to create a lasting positive impact since the third quarter of 2023.

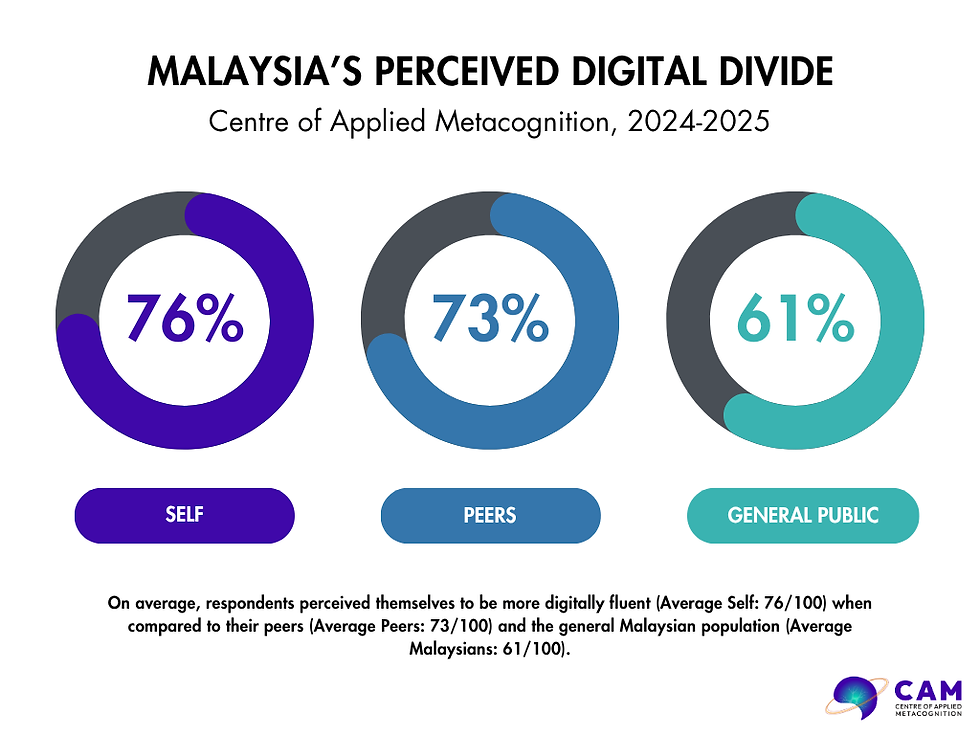

However, the findings also reveal a potential risk of overconfidence. Respondents tended to rate their own digital fluency (76.25) higher than that of their peers (72.63) and the average Malaysian (60.88).

While self-efficacy is vital, this disparity suggests that many people may believe they have somewhat achieved digital mastery, while still seeing a long way to go for everyone else in the nation. This perceived gap between personal confidence and national readiness is what we call the Digital Readiness Illusion.

In recent years, the Malaysian government has been actively driving digital transformation in recognition of the importance of nation-wide digital mastery. The establishment of the National Artificial Intelligence Office (NAIO) and the popular “AI untuk Rakyat” programme show commitment to steering Malaysia towards being an AI producer and an international contender in the AI industry, especially in the ASEAN region. These top-down initiatives, supported by significant budget allocations and new legislation like the Personal Data Protection Act and the Cybersecurity Bill, are foundational to building trust and infrastructure.

Malaysia’s Effort in Driving AI Transformation

In December 2024, Malaysia established the National Artificial Intelligence Office (NAIO) under MyDIGITAL Corporation, with a mandate to steer Malaysia from merely consuming AI to being a producer of AI solutions. NAIO’s responsibilities include formulating national strategy and policy frameworks, overseeing AI governance and ethics, fostering collaboration between academia, industry, and government, and building up public trust.

At the same time, the “AI untuk Rakyat” programme under Rakyat Digital seeks to democratise AI awareness by offering a free online, self-learning course on basic AI knowledge. So far, 1.39 million learners have enrolled.

Malaysia is also making moves to assert regional leadership. In August 2025, the country hosted the ASEAN AI Malaysia Summit (AAIMS25), bringing together more than 1,500 delegates and over 150 exhibitors to discuss AI sovereignty, regulatory harmonisation, talent development, and security.

To support these efforts, Malaysia has been putting in place legal and regulatory foundations: in the 2025 Budget, RM10 million was allocated for the National Artificial Intelligence Office (NAIO); and new legislation such as amendments to the Personal Data Protection Act, a Cybersecurity Bill, and a Data Sharing Bill have all been enacted and are now fully enforced or in the final stages of a staggered enforcement.Despite these efforts and the high confidence found in our survey group, achieving true national digital mastery faces significant bottom-up hurdles. Why is this so?

Previous research⁴,⁵,⁶ on digital habits of Malaysian youths reveal several factors that slow personal and nationwide digital mastery in Malaysia:

Language Barriers: Digital literacy is often heavily dependent on English competency, which can discourage the utilisation of digital content for informational and educational purposes.

Passive Consumption: There is a trend towards passive consumption of digital content from the Internet and social media, rather than active engagement.

Limited Critical Evaluation: Youths struggle to infer the overarching themes and meanings in digital content and rarely evaluate its credibility, authenticity, or reliability.

Low Patience: Limited attention spans encourage skimming through articles and skipping from website to website, resulting in only surface knowledge and ideas. (Read more about outsourcing brains to AI in this article)

In a broader regional context, a survey on digital literacy amongst ASEAN youths⁷ had found that:

There is a large disparity between ASEAN countries in terms of digital literacy education provided in schools.

Many youths struggle to gain digital literacy due to a lack of access to digital devices, stable Internet, and insufficient technical infrastructure provided in schools.

Pro-active approaches like extra-curricular courses are not popular amongst youths as primary methods for developing their digital literacy.

A study on digital literacy amongst ASEAN countries⁸ had ranked Malaysia seventh out of eight with an average ranking score of 19.20, behind Singapore (24.6), Thailand (24.0), Indonesia (20.5), and Vietnam (20.4), Myanmar (19.9), and Philippines (19.80), with only Cambodia (15.60) ranking lower. Although digital literacy levels between one country and another were found to be not significantly different, this ranking still suggests that despite the high confidence level found in our educated survey group, there is still a marked challenge in digital literacy penetration across the nation.

The Need for a Bottom-Up Approach

The survey's main takeaway is that Malaysians are not resistant to AI; they are ready and confident in their ability to learn. The challenge now is to leverage this positive mindset to bridge the gap between intention and behavior, and to turn the current high self-assessment into actual national mastery.

Tackling the deep-seated issues of passive consumption and limited critical thinking requires a shift from a purely top-down approach to one that focuses on individual behavioral change and skills development from the ground up, with interventions at multiple levels:

In the Workplace: Beyond training, organisations need to provide the infrastructure for AI adoption, such as secure access to digital tools, clear data governance policies, and internal platforms where employees can experiment safely. Celebrating early adopters and sharing success stories helps create a culture where AI feels approachable and valuable.

In Schools: Students not only need to learn digital literacy but also build their digital confidence. This means engaging with hands-on projects, experimenting with real tools, and having a safe space to try, fail, and try again. Schools need reliable internet, functioning devices, and collaborative platforms so students can practice what they learn in real-world contexts.

At the Societal Level: Access to affordable devices and high-quality internet remains foundational. Without these, digital transformation risks deepening the gap between urban and rural, privileged and underserved communities. Addressing data security concerns is also crucial for building public trust.

The challenge now is to provide targeted education and training that transforms digital consumption into active, critical engagement and boosts the national digital literacy average.

Curious to know your own digital fluency score?

To move your team beyond the Digital Readiness Illusion and ensure they develop critical skills for the AI era, explore the Human-AI Training Programs offered by us at Otti Neurolearning Institute. We help your organisation become irreplaceable by AI, no matter how advanced AI becomes.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998).

Asha. (2023, November 20). Malaysian’s Perception of Artificial Intelligence. Www.oppotus.com. https://www.oppotus.com/malaysians-perception-of-artificial-intelligence/

Tan, K. E., Ng, M. L., & Saw, K. G. (2010). Online activities and writing practices of urban Malaysian adolescents. System, 38(4), 548-559.

Shariman, T. P. N. T., Razak, N. A., & Noor, N. F. M. (2012). Digital literacy competence for academic needs: An analysis of Malaysian students in three universities. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 1489-1496.

Abidin, M. J. Z., Pour-Mohammadi, M., & Jesmin, A. (2011). A survey of online reading habits of rural secondary school students in Malaysia. International Journal of Linguistics, 3(1), 1-18.

UNICEF. (2021). Digital literacy in education systems across asean. Key insights and Opinions of Young People. Retrieved from Digital Literacy in Education Systems Across ASEAN, UNICEF East Asia and Pacific.

Kusumastuti, A., & Nuryani, A. (2020, March). Digital literacy levels in ASEAN (comparative study on ASEAN countries). In IISS 2019: Proceedings of the 13th International Interdisciplinary Studies Seminar, IISS 2019, 30-31 October 2019, Malang, Indonesia (p. 269). European Alliance for Innovation.

Published on: 27 November 2025

Written by: TING Shu Jie, CHANG Yin Jue

© 2025 Centre of Applied Metacognition (CAM)

Comments